“It opens up all these new horizons for art history, for connoisseurship, and for how the discipline is going to continue to form.”

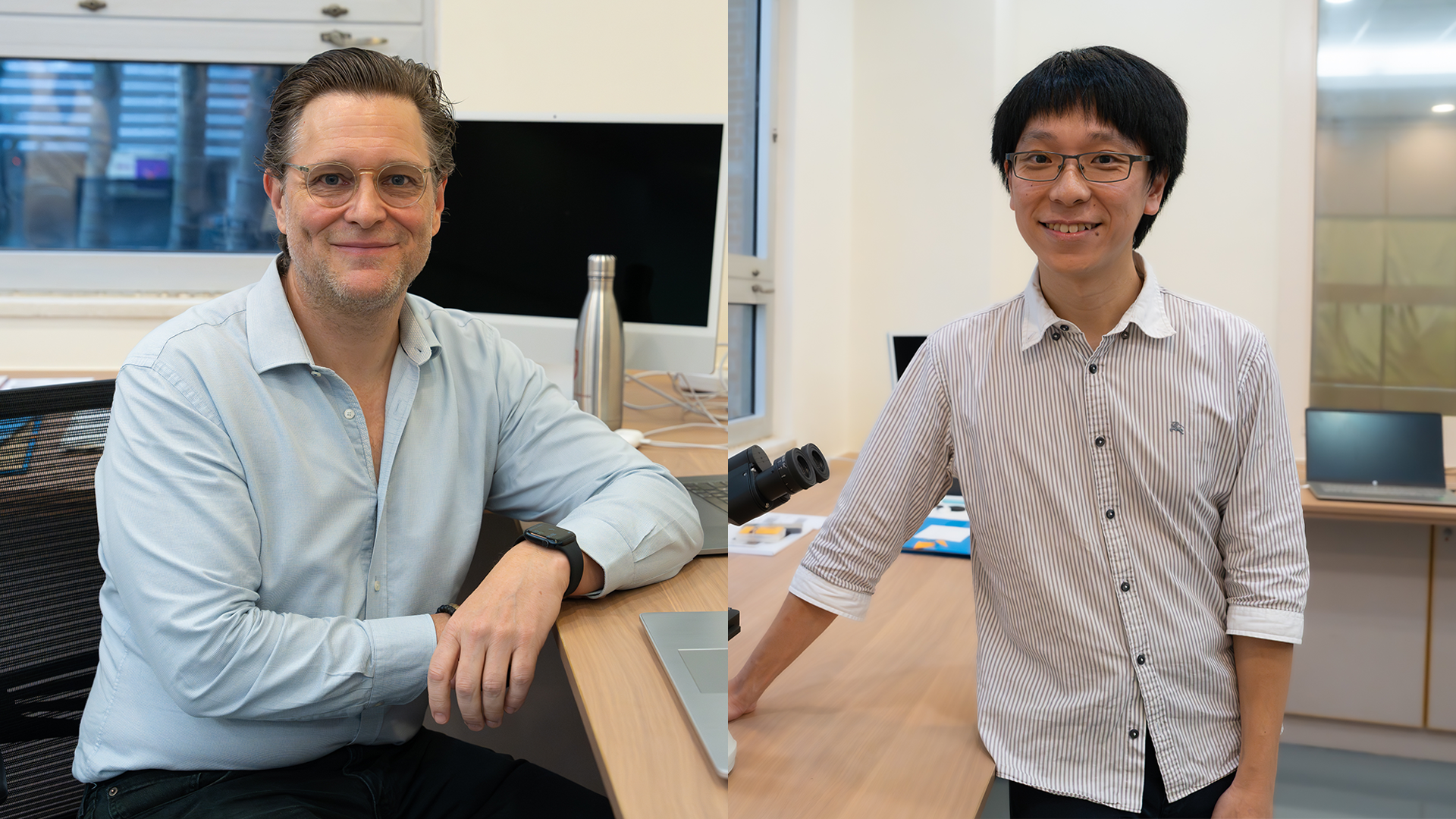

— Professor Marc Walton

You’ve heard of using AI to make art, but an interdisciplinary team of researchers at the University of Hong Kong is now tackling a far more complex problem: applying AI to the field of art conservation. Their work could have outsize ramifications for the world’s art institutions, expanding access to cutting-edge art conservation tools, cutting the time needed for materials analysis and allowing even small museums to protect and preserve their collections.

A Hands-On Approach

Tucked away in a corner of the Hong Kong University Museum and Art Gallery is the only on-site, university museum research lab in Asia. There, a team of chemists, conservation scientists, and students under Professor Marc Walton of HKU’s Museum Studies programme and the Department of Chemistry’s Dr Kenneth Ng are developing, building, and experimenting with new instrumentation that could radically lower the barriers to characterising the materials comprising objects of art and archaeology.

Looking around the lab, it’s hard to imagine that, a little over a year ago, almost none of this infrastructure existed. Before Walton, who was previously Head of Conservation and Research at M+, joined HKU in 2024, he had never met Dr Ng. They were brought together by another new arrival to the university, Chemistry Professor Jay Siegel, who recognised the pair’s shared interest in both chemistry and mechanical tinkering.

For Professor Siegel, the collaboration offered a solution to two longstanding issues in university education: how to break down barriers between disciplines and give students hands-on experience with real-world applications.

“(The students) are very well trained, they know their theories, but they’ve never touched an artefact before.”

— Dr Kenneth Ng

Soon, what began as a series of informal conversations morphed into something very real, with Walton joining HKU, then teaming up with Ng and the Chemistry department to bring their vision to life. “Jay recognised that Kenneth and I were thinking along the same lines,” says Walton. “He couldn’t have been more correct. This is the type of cross-fertilisation you normally wouldn’t think about: bringing a chemist together with someone from the humanities.”

Bridging Art and Science

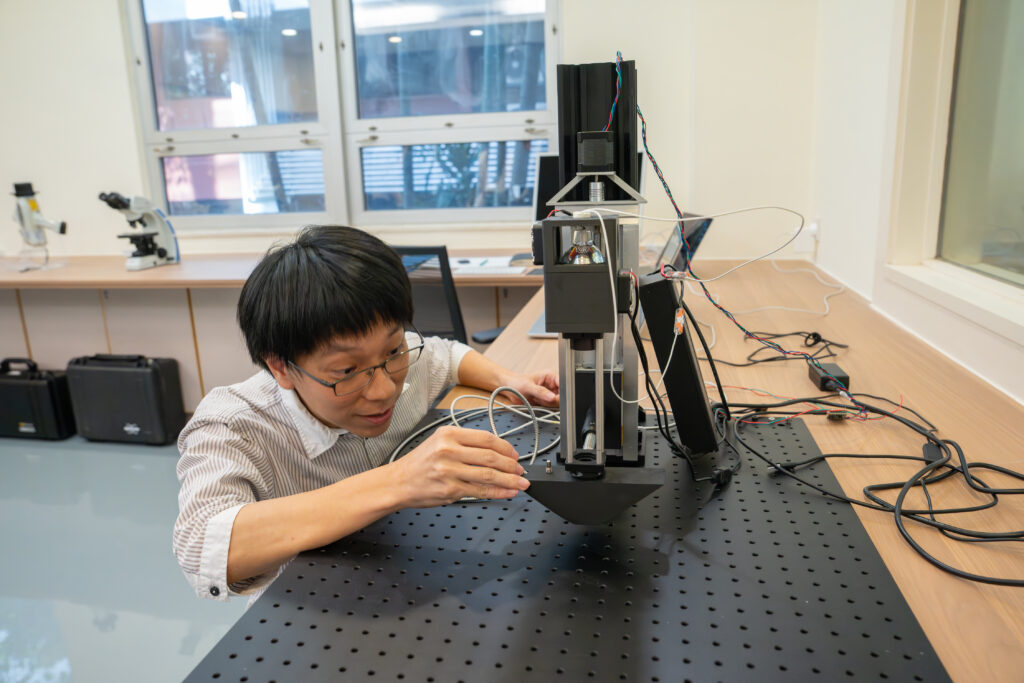

Viewed from the front, the UMAG lab’s “Franken-camera” doesn’t look particularly unusual. It’s only when you circle around back that the moniker’s logic starts to come into focus, revealing uncovered wires and chips that have been grafted on by the team to improve performance.

The Franken-camera is far from the only curious-looking tool in the lab. The team uses a wide variety of analysis instruments, from off-the-shelf items like the handheld XRF spectrometer – designed to mimic the look of a Star Trek phaser – and modified microscopes. Their commitment to home-brewed tech isn’t just about performance or customisability; by opting to custom build tools, they give students more opportunities to practice a variety of skills that could be useful for their futures, such as the integration of code with hardware.

“The one big hurdle that we face in teaching is that ‘fancy’ microscopes are usually very, very expensive and ‘thou shalt not touch it.’”

— Dr Kenneth Ng

One of the biggest new tools in their toolkit is artificial intelligence. While the underlying machine-learning tech has been around for decades, the proliferation of LLMs and AI applications is drastically shortening the time spent on materials analysis – a key step in the process of understanding and conserving a piece of art.

As an example, Walton points to the traditionally time-consuming task of point analysis of artefacts. AI is allowing the team to take a handful of data points – some with detailed spectroscopic information, others that cover a larger portion of the artefact and show spatial details – and merge the sets to produce an image cheaply and quickly.

Expanding Access Through AI

“AI allowed us to do that. Before, it was really difficult to be able to fuse these different things together, to be able to create something that combines the best of both worlds.”

— Professor Marc Walton

Both Walton and Ng spotlight AI’s impact in expanding access to art conservation. Traditional conservation characterisation methods are expensive and difficult to use, leaving institutions across the globe struggling to balance their desire to augment the value of their collections through study and treatment with the associated costs of bringing science into the museum.

If the cost of conservation tools and processes could be brought down, the thinking goes, then many of these problems could be solved with some basic technical knowledge and a little ingenuity.

“These are things that any museum around the world, any person that’s interested in duplicating our work, could conceivably be able to do it without spending a whole lot of money,” says Walton.

The Future as Blank Canvas

The team cautions that AI isn’t a cure-all, and that many of the classical methods of conservation continue to work well. Rather than completely overturning the field’s received knowledge, they’re focused on teaching students how to develop and use new tools while maintaining a critical mindset.

“It’s very important for students to know the nuts and bolts of AI rather than just using it as a black box,” says Ng, using a common metaphor for the opacity of AI algorithms. “Especially as a scientist, you really need to put on that scientist hat and differentiate whether it’s hallucinating, or whether it’s giving you the right answers.”

Still, they remain excited about the tech’s potential for conservation, with Walton pointing to possibilities, not just for the museum world, but also for lowering the barriers to connoisseurship and changing the field of art history.

That’s not all: Asked whether AI can bridge the gap between objective and subjective analysis, Walton pauses for a moment before turning philosophical. “I always think the objective and subjective come together, because the agency of the artist is in the materials, which we can be objective about” he says. “But really, what we want to understand is the subjective part of it. So, we’re using science as a tool to assess the subjective.”

To learn more about how Professor Walton and Dr Ng are using AI to rewrite the rules of art conservation, watch the video below: