Forests aren’t the only fragile ecosystems at risk from climate change. In the right conditions, Sargassum, a kind of macroalgae, can trap vast amounts of carbon and store it at the bottom of the ocean. But what happens when those conditions change?

The University of Hong Kong’s Professor Wang Mengqiu doesn’t want to wait to find out. Working with satellite imagery and advanced AI algorithms, she’s tracking oceanic conditions, monitoring blooms, and trying to answer an all-important question: How much of a given Sargassum bloom will become a carbon sink – and how much will wind up a carbon source?

Across the sea

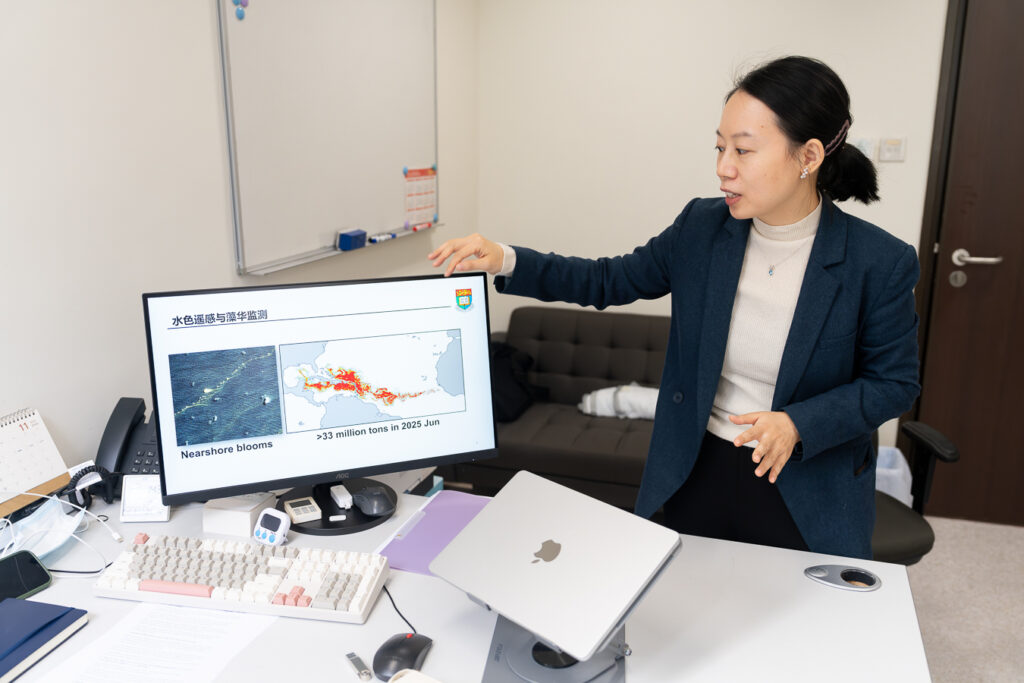

The scale of Sargassum blooms can be hard to comprehend. To demonstrate what the planet is facing, Professor Wang pulls up a map showing the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, which stretches from the western coast of Africa across the ocean to the Caribbean and Mexico.

A recurring natural phenomenon, the Belt was observed as early as the late 15th century. “The ocean can benefit from Sargassum,” Professor Wang says, adding that they are “very big players in the ocean carbon cycle.”

Yet the Belt’s recent growth has worried researchers, as blooms set historical highs and landfall events in the Western Atlantic smother beaches and coastal wildlife.

“Satellites are an ‘eye in the sky,’ giving us a synoptic view of what’s happening below.”

– Professor Wang Mengqiu

“In the open ocean, Sargassum acts as a carbon sink,” Professor Wang explains. “But if it reaches the coast, it releases hydrogen sulfide (a compound linked to asthma) and endangers coastal vegetation, including corals and seagrasses.”

Step one in addressing the problem is figuring out just how large the Belt has become – and where and when landfall events are likely to occur. But how do you measure something that spans an entire ocean?

AI in the sky

Typically, tracking Sargassum blooms might involve observations from a boat.

Both of these methods are expensive and time-consuming. So researchers like Professor Wang are turning to satellite and remote sensing technology, leveraging tools like AI and big data to quickly and efficiently identify Sargassum patches and map their locations.

Using satellites designed to monitor colour changes in the ocean, scientists can get a much better idea of how big the Belt – actually a thousands-of-miles-long stretch of discrete blooms – really is.

Although the underlying technology has been around since the 1980s, the field has benefitted in recent years from new hyperspectral sensors, higher-resolution images, and the shift from machine learning to deep learning.

“We don’t want to just react, we need to be able to make predictions.”

– Professor Wang Mengqiu

The launch of NASA’s Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem (PACE) Satellite in 2024 was particularly exciting, Professor Wang says. “The satellite is a game changer because it’s hyperspectral,” she explains. “It will give us a much finer, more detailed knowledge of global changes.”

Previously, that level of detail would have been hard to analyse. But new deep learning techniques are making even hyperspectral imaging analysis possible, Professor Wang says. Her own work is one reason why: She just published a paper showing how to automatically de-noise images to better monitor algal blooms.

These advances will ultimately make it easier for scientists to predict the size and impact of future blooms, allowing for better management and mitigation.

The search for solutions

Professor Wang’s next project is to develop algal bloom distribution maps that can be used to guide policymaking.

The Atlantic isn’t the only ocean facing growing problems related to Sargassum. In the Yellow Sea and East China Sea, for instance, blooms have caused havoc in recent years.

Professor Wang hopes to work together with the Hong Kong government to understand public needs and design real-world applications for researchers’ growing trove of remote sensing data, including alarm systems for Sargassum landfall.

“The goal is to convert Sargassum into something useful: energy, building materials, or other applications.”

– Professor Wang Mengqiu

While these ideas are still a long way off, she believes they could one day help mitigate or even eliminate the damage done by Sargassum to coastal ecosystems like Hong Kong’s – and even help vulnerable populations like the city’s fishers.

“I want to convert satellite products into something broadly useful,” she says. “As scientists, we have to serve the community.”