In just 40 years, China went from a predominantly rural society to a highly urbanised one. What happened? And what lessons can other urbanising regions around the globe draw from that experience?

University of Hong Kong Professor of landscape architecture Bin Chen believes we can find the answers in satellite data. An expert in remote sensing and Director of HKU’s Future Urbanity and Sustainable Environment (FUSE) lab, he’s using satellite imagery to track everything from the historical growth of cities to emerging problem areas like urban heat, air pollution, and green/blue space loss.

It’s a cutting-edge field – and one with implications far beyond China. Done correctly, it could provide one of the first-ever windows into how cities grow and evolve in the real world. This emerging “urban intelligence” will in turn have major ramifications for rapidly urbanising countries across the Global South, allowing them to avoid mistakes made by other cities while empowering them to create more equitable built environments for all residents.

We asked Professor Chen to share his thoughts on the nature of his work, the importance of remote sensing and AI to urban planning, and how the world can build more equitable cities.

The “intangibles” of sustainability

Professor Chen characterises his work as looking at the “tangibles and intangibles” of the built environment.

The tangibles are relatively straightforward. But the intangibles – air, heat, sunlight, light pollution, shade, and noise – play just as important a role in our lives and health, while being much harder to quantify.

That’s where satellites can play a role, Professor Chen says, as new data and methods allow researchers to look at cities on a granular level, identifying problematic heat islands, light pollution, and air quality.

“It’s not just about climate. It’s also about liveability.”

– Professor Bin Chen

Importantly, these are also problems of equity and ESG, with poorer residents often having to go without access to parks, shade, and clean air.

“Take shade, for example,” Professor Chen says. “In a city of high-rises, where you have people living in subdivided units with no access to sunlight year-round, shade is a social issue.”

Even if every building in a given district meets regulations, it can be hard to tell what the overall outcome will be – a problem satellite imagery and AI modelling can help solve.

While Professor Chen’s team can identify the issue, he hopes work on the solutions will be an interdisciplinary affair. “We need to bring experts together,” he says. “We need knowledge from social economics, environmental studies, data science, and urban planning.”

Urban intelligence

The long-term goal is to develop what Professor Chen calls “urban intelligence” – a deeper understanding how people, cars, buildings, and the environment interact – then apply that knowledge to developing regions around the world.

Perhaps surprisingly, given their importance in modern life, the actual mechanisms by which cities grow are not always well understood. It wasn’t until 2008, when satellite data became more widely accessible, and 2015, when large-scale cloud computing and machine learning caught up, that researchers could closely examine the growth of modern cities.

“AI makes everything more efficient.”

– Professor Bin Chen

Professor Chen points to Shanghai’s Pudong New Area as a classic example, noting that while policy documents offer a window into its growth, remote sensing technology allows researchers a seamless, transparent view of how the district grew into a global financial capital.

Leading the way

But taking advantage of these advances will require more – and more open – data.

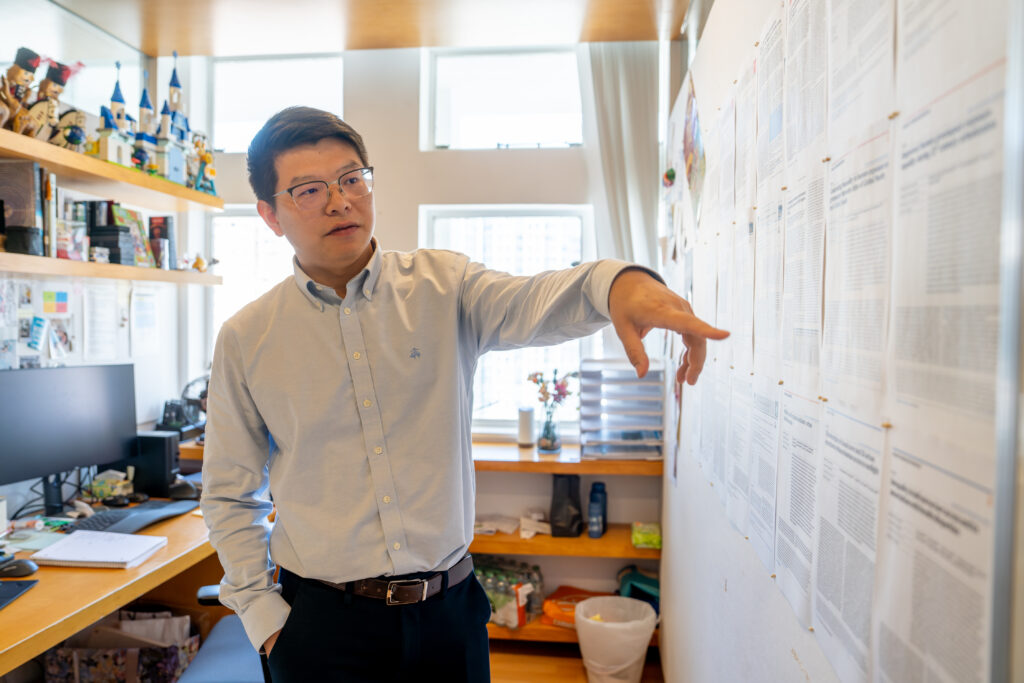

Still, researchers can make significant progress via virtual collaborations. A few years ago, Professor Chen worked with HKU Professor Peng Gong and partners from 23 universities and institutes across China on a database of Chinese urban land use.

By mixing satellite data with on-the-ground verification, they were able to create the country’s first nationwide parcel-level essential urban land use categories map, allowing researchers to easily compare cities around China, from Beijing to Shenzhen and Wuhan.

“Remote sensing is becoming more and more powerful. We used to have to focus on individual cities, but now we can look at entire countries, even the whole globe.”

– Professor Bin Chen

That empowered numerous follow-up studies, and the team hopes to expand their map to the rest of the world in the coming years.

“We’re entering a new stage, going beyond remote sensing with multimodal data,” says Professor Chen. “But pushing the field forward will require more data sharing.”